Highlights

- Northern China Rare Earth Group operates as a state-controlled strategic node within China's command framework, with SASAC ownership ensuring decisions align with national industrial policy rather than market forces alone.

- Controlling the world's largest rare earth deposit at Bayan Obo (83% of China's reserves), the company dominates global light rare earth production while maintaining deliberately low profit margins to support China's downstream manufacturing competitiveness.

- China's vertically integrated, policy-driven rare earth system creates structural asymmetry against fragmented Western supply chains—recent export controls caused magnet prices to spike 5-6x and forced Ford to idle EV production, demonstrating weaponized supply leverage.

When Western policymakers talk about China’s dominance in rare earths, they often imagine a loose web of mines, refiners, and exporters. In reality, the core of China’s rare earth power is highly centralized, state-backed, and institutionally disciplined. At the center of that system sits Northern China Rare Earth Group (600111.SS) – the world’s largest rare earth producer by volume and the anchor of China’s northern rare earth complex. This company is not just a miner or refiner; it is effectively an operating arm of Chinese state strategy embedded within a command framework.

Table of Contents

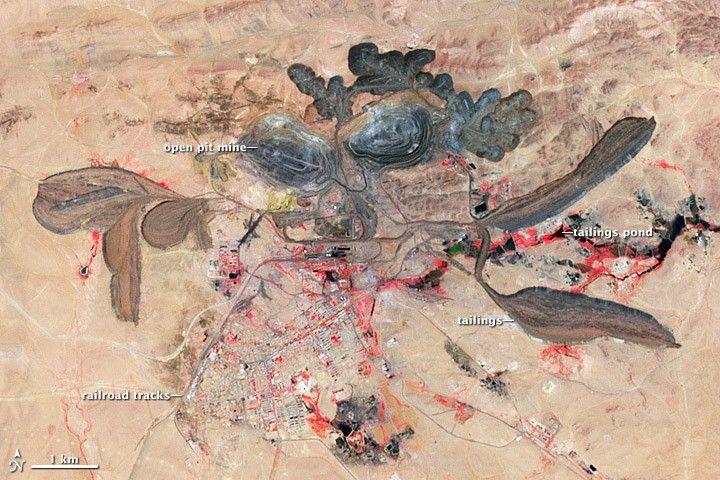

Satellite image of the Bayan Obo rare earth mining complex in Inner Mongolia, controlled by Northern Rare Earth Group.

The two large circular open-pit mines and multiple tailings ponds (green and black areas) underscore the vast scale of operations. By the early 2010s, this single site supplied roughly half of the world’s rare earths via NASA.

A Company, a Parent, and the State

Northern China Rare Earth Group (opens in a new tab) (formerly Baotou Rare Earth) is publicly listed on the Shanghai Stock Exchange, but it is not “public” in the Western sense. Its controlling shareholder is Baogang Group (opens in a new tab) (Baotou Iron & Steel Group), a major state-owned enterprise (SOE). Above Baogang sits the ultimate owner and governor: the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council (opens in a new tab) (SASAC). In other words, Northern Rare Earth is nested within a layered SOE hierarchy, answerable to China’s central state capital apparatus.

This structure matters. Northern Rare Earth’s decisions are not driven solely by market forces or private shareholder interests. Instead, it operates inside a state-capital command framework. Production targets, pricing discipline, export behavior, environmental compliance, and long-term investments are all aligned with directives from the state. The firm’s leadership is appointed and evaluated by SASAC, and its strategy serves national industrial policy goals rather than just quarterly profits. In effect, Northern Rare Earth behaves less like an autonomous corporation and more like a strategic node in China’s industrial policy machine.

Scale, Assets, and Market Power

Northern Rare Earth controls access to the Bayan Obo deposit in Inner Mongolia – the world’s largest known rare earth ore body by content. This single mining district accounts for about 83% of China’s rare earth reserves and produces the lion’s share of China’s light rare earth elements (LREEs). Through integrated mining, separation, and refining operations, Northern Rare Earth dominates output of key light rare earths such as neodymium and praseodymium (NdPr), the critical ingredients in high-strength permanent magnets used for electric vehicle motors, wind turbines, electronics and defense systems.

By volume, Northern Rare Earth is the world’s largest rare earth mining company. China’s overall rare earth mine production was 270,000 metric tons in 2024 (about 69% of global output) noted in China Briefing (opens in a new tab) by Dezan Shira and Associates and Northern Rare Earth – as the principal operator of Bayan Obo – contributed a major portion of that. With its parent Baogang, it effectively serves as gatekeeper for raw feedstock that supplies China’s downstream magnet alloy and materials industry. This throughput control is the true source of its power: by managing the spigot of rare earth oxide supply, Northern Rare Earth holds sway over the inputs that countless manufacturers rely on.

Financially, the company’s revenues can surge into the tens of billions of yuan in high-price years. However, its profitability is deliberately kept modest – a reflection of policy goals to stabilize prices and support value-added manufacturing. In 2024, Northern Rare Earth’s operating margin was only about 5.6%, (opens in a new tab) a slim figure compared to Western mining majors. This underscores that maximizing profit is secondary to maintaining state-guided supply and price stability. By design, Northern Rare Earth tolerates lower margins (but massive volume) to keep China’s magnet supply chain competitive globally.

The company has also been expanding its capabilities across the value chain. Recent state-media updates highlight that Northern Rare Earth completed a “Green Smelting Upgrade”, making its separation and smelting facility the largest of its kind in the world as reported by Rare Earth Exchanges (REEx). It also launched an integrated price-publishing and trading platform for rare earth products. These moves further institutionalize China’s influence over rare earth pricing and distribution – reinforcing that Northern Rare Earth is not just a producer, but a system coordinator within China’s rare earth sector.

SASAC HQ

SASAC:The Owner Behind the Curtain

To understand Northern Rare Earth’s behavior, one must understand SASAC, the agency that acts as the state shareholder for China’s central SOEs. SASAC is not a regulator in the Western sense; it is the arm of the state that exercises ownership rights over key enterprises on behalf of the central government. Created in 2003 and grounded in State Council regulations (and later the 2008 Law on State-Owned Assets), SASAC has authority to appoint top executives, approve mergers or restructurings, set performance targets, and enforce financial discipline in central SOEs.

As of 2025, SASAC oversaw (opens in a new tab) 96 centrally-administered SOE groups, with total assets exceeding ¥90 trillion (≈$12 trillion) and annual profits around ¥2.6 trillion (≈$360 billion). These enterprises span China’s strategic backbone industries – energy, metals/mining, telecommunications, aerospace, shipping, steel, defense manufacturing, and more. Northern Rare Earth falls squarely into this universe as part of China’s strategic minerals and materials portfolio.

Recent SASAC directives shed light on the priorities guiding companies like Northern Rare Earth. In 2024, SASAC announced that stock market value management will be included in SOE executive evaluations, pushing listed SOEs to pay more attention to their valuation and investor returns. SASAC also explicitly barred central SOEs from diversifying into financial investments, refocusing them on their core industrial missions. Moreover, the emphasis has shifted from managing individual enterprises to managing state capital as a whole – meaning SASAC encourages mergers, consolidations, and portfolio adjustments to better serve national strategic objectives. (The creation of China Rare Earth Group in 2021 by merging several southern rare earth firms is a prime example of this strategy to streamline state assets.)

For Northern Rare Earth, this context means its production discipline, consolidation moves, environmental compliance, and export posture are not discretionary corporate choices – they are policy-aligned mandates. The company’s output is capped by state-imposed quotas, and it must coordinate with its counterpart (the China Rare Earth Group) to redistribute quotas to subordinate units across regions. Environmental standards are enforced not just by regulators but through SASAC’s oversight, which treats issues like pollution or resource waste as threats to state asset value. In short, Northern Rare Earth operates under an owner’s guidance that prioritizes long-term national interest and supply security over short-term profit or free-market competition.

Why This Matters to the West

For the U.S. and its allies, Northern China Rare Earth Group illustrates a structural asymmetry in the global rare earth supply chain. On one side is China’s state-integrated system, epitomized by Northern Rare Earth’s alignment with government policy. On the other side are Western and other international efforts, which remain largely fragmented and market-driven – a patchwork of junior mining firms, independent refiners, separate magnet alloy producers, and multiple national jurisdictions struggling to coordinate.

This contrast is architectural, not just ideological. China has spent decades building a vertically integrated rare earth powerhouse: from resource ownership (state control of mines like Bayan Obo) to processing (state-backed separation plants), to downstream manufacturing (magnet factories supported by industrial subsidies), all governed under a unified strategic umbrella. The result is a supply chain that Beijing can orchestrate as one organism.

When Beijing wants to tighten supply or enforce discipline, it can use administrative levers – quotas, export licenses, environmental crackdowns – that take immediate effect through companies like Northern Rare Earth.

Western countries, by contrast, face inherent hurdles in responding in kind. Supply chains outside China involve multiple private companies in different countries, each guided by profit motives and subject to separate regulations.

Opening a new mine in the U.S. or Australia is just one piece of the puzzle– it does not automatically create local processing ormagnet-making capacity. Indeed, mined concentrates from the West often still end up shipped to China for refining. Simply put, adding more non-Chinese mines does not neutralize Beijing’s advantage when China dominates the more complex stages of refining and metallurgy (over 90% of rare earth refining as of 2024).

China’s leverage is not theoretical; it has been demonstrated. In 2010, after a diplomatic dispute, China suspended rare earth exports to Japan, causing rare earth prices to spike by up to ten-fold and crippling Japanese tech manufacturers. More recently, in 2025, China imposed new export controls on certain rare earth elements and magnets as tensions with the West grew. Within weeks, global supply disruptions hit: for example, Ford Motor Company had to temporarily idle an EV factory in Chicago due to a magnet shortage, and a Ford executive described the supply chain as living “hand to mouth.” European officials likewise reported prices for some rare earth magnetssoaring to five or six times higher outside China than inside China after the export curbs.

Western defense contractors, too, grew alarmed as these Chinese measures threatened supplies of specialized magnet alloys needed for missiles, jet fighter electronics, and radar systems. In a fiery speech, the European Commission president accused China of “weaponizing” its dominance of rare earths – a stark reminder that control of these materials is a geopolitical instrument.

Leadership

| Leader | Role |

|---|---|

| Liu Peixun | Chairman of the Board; Party Secretary |

| Qu Yedong | General Manager/President; Director; Deputy Party Secretary |

| Song Ling | Chief Financial Officer / Financial Director; Director (Accounting Supervisor) |

| Yonggang Wu | Secretary of the Board; Chief Compliance Officer; Director |

| Rui Han | Deputy General Manager |

| Hua Lian | Deputy General Manager |

| Zhao Zhihua | Chief Engineer |

| Ying Du | Independent Director |

| Cheng Wang Chen | Chairman prior |

Final Thoughts

The strategic implications of this asymmetry are profound. Rare earth elements—the neodymium in electric motors, samarium in precision missiles, terbium in semiconductor substrates—sit at the heart of modern power, from electric vehicles and wind turbines to fiber-optic networks and advanced military systems. A single U.S. F-35 fighter contains hundreds of kilograms of rare-earth-dependent components. If China were to disrupt exports of processed rare earths or magnets, production timelines across defense, energy, and advanced manufacturing could be compromised almost immediately. This is not a hypothetical vulnerability; it is a structural one.

Northern Rare Earth’s operating model illustrates what supply-chain security looks like from Beijing’s perspective. Integration across mining, separation, refining, and downstream manufacturing—backed by state capital and enforced through policy (and potentially military if supply chains continue to be militarized)—allows China to manage prices internally, favor domestic manufacturers, and deploy exports as a calibrated lever. Environmental “inspections,” quota adjustments, or licensing changes can ripple through global markets overnight not because rare earths are scarce, but because China has engineered a policy-driven chokehold across the value chain.

For the U.S. and its allies, competing with this system requires far more than opening new mines in California or Australia. As REEx continues to convey, this demands sustained policy coordination, public-private capital alignment, and downstream build-out at a scale rarely attempted outside wartime.

Early steps—Defense Production Act funding, the CHIPS Act, the Inflation Reduction Act, and allied initiatives like the Mineral Security Partnership during Trump 1.0 and Biden, followed by an appropriately more aggressive Trump 2.0’s Executive and 232 Actions, tariffs and DoD, DoE DoC investments and grants—signal growing recognition that market forces alone will not secure critical materials.

Yet these efforts remain fragmented compared with China’s decades-long, centrally orchestrated approach. We are talking about different models here. The unavoidable conclusion is architectural: breaking China’s rare-earth leverage will require not just geology, but a rethinking of how the West organizes capital, permits infrastructure, and integrates raw materials into industrial and defense planning, processing and production.

©!-- /wp:paragraph -->

0 Comments