Highlights

- Southeast Asia emerges as a consequential force in global critical minerals with substantial reserves in nickel, tin, bauxite, and rare earths, but faces structural fragmentation and uneven national strategies that limit regional cohesion.

- Indonesia's nickel export ban exemplifies rising industrial policy activism, successfully building domestic smelting capacity while deepening dependence on Chinese capital amid U.S.-China supply chain bifurcation.

- ASEAN's mineral opportunity hinges on strengthening regulatory alignment, ESG compliance, and coordinated downstream integration to avoid remaining merely a supplier of intermediate materials rather than a full-spectrum value-chain competitor.

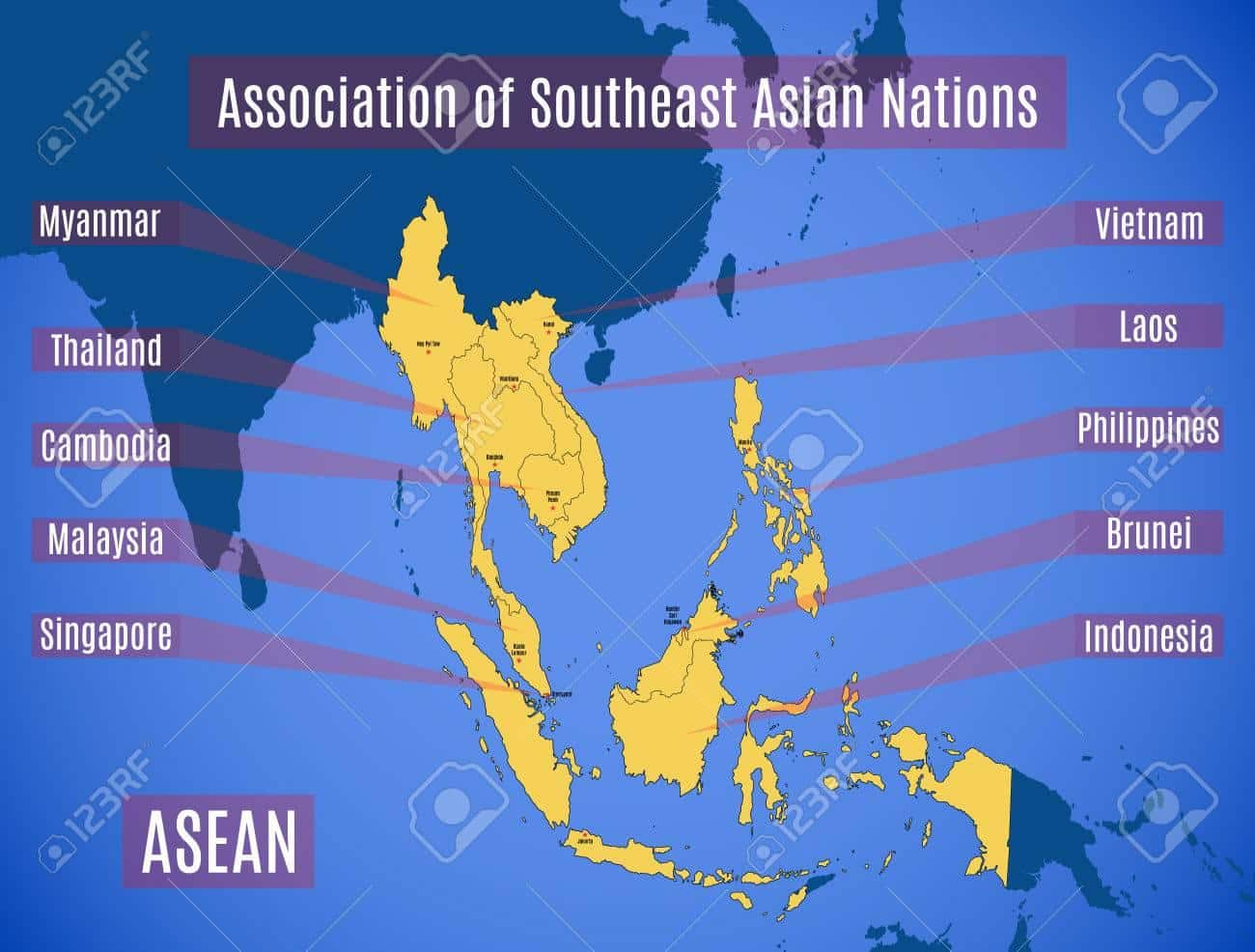

The next key player? Assessing The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (opens in a new tab) (ASEAN) role in global critical minerals supply chains, Dr Pia Dannhauer (opens in a new tab), Senior Research Fellow at the Perth USAsia Centre (opens in a new tab), argues (opens in a new tab) that Southeast Asia is emerging as a consequential force in global critical mineral supply chains—but faces structural fragmentation, geopolitical crosswinds, and rising sustainability pressures that may limit its ascent. As demand for lithium, nickel, rare earths, graphite, and other transition minerals accelerates alongside global energy and digital transformation, ASEAN has adopted a long-term ASEAN Minerals Development Vision (AMDV) (opens in a new tab) to 2045 and the ASEAN Minerals Cooperation Action Plan IV (AMCAP-IV, 2026–2030) to position the region as a leading destination for critical minerals investment. Yet uneven national strategies, heavy reliance on China for refining and downstream processing, governance gaps, and deepening U.S.–China supply chain bifurcation complicate ASEAN’s ambition to become a strategically autonomous player.

Study Approach

This brief is a strategic policy analysis rather than a geological or econometric study. Dr Dannhauer synthesizes ASEAN production data, institutional frameworks, and geopolitical dynamics to evaluate the region’s collective trajectory. The paper situates ASEAN within broader global trends: accelerating mineral demand, industrial policy activism, ESG scrutiny, and supply-chain “de-risking” efforts by the United States and its partners.

Key Findings Explained

1. Resource Strength, Institutional Weakness

ASEAN collectively holds substantial reserves—particularly in nickel (Indonesia and the Philippines), tin (Malaysia and Indonesia), bauxite (Indonesia and Vietnam), and rare earths (notably Myanmar and Malaysia). However, member states differ widely in economic structure, regulatory quality, and industrial policy capacity. This fragmentation limits ASEAN’s ability to act as a cohesive supply-chain bloc.

2. Industrial Policy Is Rising—But NotCoordinated

Indonesia’s 2020 nickel export ban is the most prominent effort to force in-country refining and value capture. It succeeded in building domestic smelting capacity but also deepened dependence on Chinese capital and ownership structures. Other ASEAN states have explored similar strategies, yet policies remain nationally driven rather than regionally harmonized.

3. Geopolitical Bifurcation Is Testing ASEAN’s Non-Alignment

China remains the dominant investor and processor in Southeast Asia’s mineral sector. At the same time, U.S.-led initiatives—such as the Inflation Reduction Act and the Minerals Security Partnership—create supply chain rules that may exclude Chinese-linked materials. This forces ASEAN states into delicate balancing acts between economic pragmatism and strategic autonomy.

4. ESG Standards Could Become a Competitive Barrier

Environmental degradation, corruption risks, and inconsistent regulatory enforcement undermine investor confidence. Emerging standards—such as the EU’s Battery Regulation and carbon border measures—may function as de facto trade barriers if ASEAN producers fail to meet higher sustainability benchmarks.

Limitations

This is a forward-looking strategic assessment, not a quantitative forecast. It does not model production curves, capital requirements, or price trajectories. Outcomes depend on domestic political cohesion, regulatory reform, and global geopolitical stability—variables outside ASEAN’s directcontrol.

Implications

ASEAN’s mineral opportunity is real—but institutional execution remains uneven. Without stronger regulatory alignment, improved ESG compliance, and coordinated downstream integration, the region risks remaining primarily a supplier of intermediate materials rather than a full-spectrum value-chain competitor.

For partners such as Australia, Japan, and the United States, engagement should prioritize governance capacity, environmental standards, and institutional harmonization—not merely upstream extraction agreements.

Conclusion

ASEAN stands at a strategic inflection point. It possesses geological endowment, growing domestic demand, and institutional ambition through AMCAP-IV and the AMDV. Yet fragmentation, geopolitical competition, and sustainability pressures cast a long shadow. Whether Southeast Asia becomes the “next key player” in global critical minerals will depend less on what lies underground—and more on governance discipline, policy coordination, and strategic clarity.

Citation: Dannhauer, Pia (2025). The next key player? Assessing ASEAN’s role in global critical minerals supply chains. Indo-Pacific Analysis Briefs, Vol. 59, Perth USAsia Centre

0 Comments

No replies yet

Loading new replies...

Moderator

Join the full discussion at the Rare Earth Exchanges Forum →