Highlights

- Researchers at Carnegie Mellon University developed a superstructure optimization model to compare end-of-life magnet-recycling routes and determine the most economical pathway before building billion-dollar facilities, testing it on hard disk drives versus EV/HEV motors.

- Hard disk drive magnet recycling is unlikely to be profitable due to insufficient concentrated feedstock, while EV/HEV motor magnets can be economically viable at modest collection rates because feedstock availability and scale dominate outcomes over chemistry choices.

- For U.S. recycled rare earth supply to succeed, policy should prioritize high-mass feedstocks like EV motors, standardized collection contracts, and automated disassembly systems, treating recycling as a specialty-chemicals operation requiring tight specifications rather than a scrap-metal business.

Chris Laliwala (opens in a new tab), Ana Torres (opens in a new tab) and colleagues at Carnegie Mellon University Department of Chemical Engineering (opens in a new tab) plus collaborators spanning Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL) and National Energy Technology Laboratory (NETL) and West Virginia University report (opens in a new tab) a practical way to “design the best recycling plant on paper” before spending billions building one: they created a superstructure optimization model that compares many end-of-life (EOL) magnet-recycling routes—step by step—to select the most economical pathway for different scrap streams, then tested it on magnets from old hard disk drives (HDDs) versus electric and hybrid vehicles (EVs/HEVs). Their central result is blunt: HDD magnet recycling, by itself, is unlikely to make money because there simply isn’t enough concentrated feedstock; EV/HEV motors, by contrast, can pencil out as profitable across wide cost ranges if modest collection rates are achieved—suggesting “urban mining” may become economically meaningful where the magnet mass per unit is high and the scrap pipeline is scalable.

Ana Torres, PhD, Principal Investigator

Study Methods

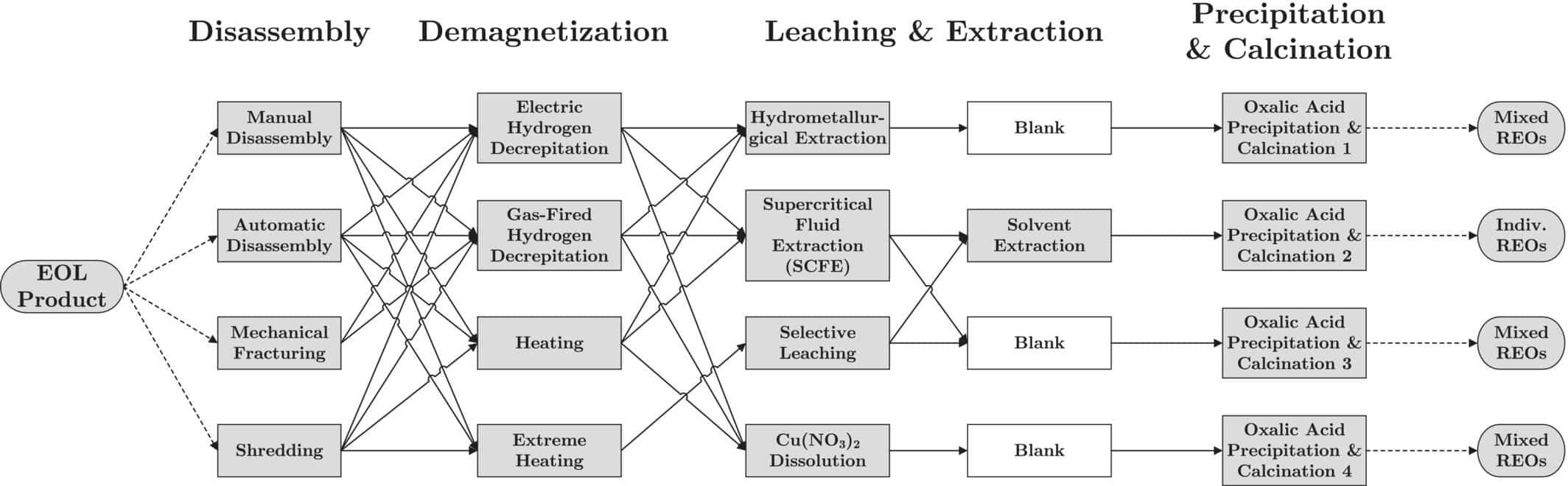

The team built a “menu” of real-world processing options across major stages—disassembly, demagnetization (including hydrogen decrepitation), leaching/extraction, and precipitation/calcination—then used optimization to pick the single best end-to-end flowsheet under two goals: maximize net present value (NPV) and minimize cost of recovery (the break-even selling price). They also introduced a new bottom-up cost model for hydrogen decarbonization equipment where public cost data are scarce.

Key findings and what they mean

1) Feedstock beats chemistry. The same “best” downstream chemistry repeatedly wins, but economics diverge mainly on feed availability and collection rates. HDDs were modeled as unprofitable (negative NPV) and would require implausibly high collection to break even. EV/HEV streams were modeled as profitable (positive NPV) and reached break-even at relatively low collection rates, indicating scale and concentration dominate outcomes.

2) Automation matters because labor dominates. For EV/HEV disassembly, automated approaches can outperform manual routes because fixed labor costs overwhelm many scenarios—an important operational signal for U.S. recycling buildouts facing tight labor markets.

Limitations and Controversies in Monitoring

This is a techno-economic/optimization study—not a full “cradle-to-magnet” demonstration. Results depend on assumed prices, discounting for mixed oxides, and collection/logistics realities that are politically and contractually hard (who owns the scrap, who pays to collect it, and at what contamination level). The modeled endpoint is rare earth oxides, not separated metals/alloys or new magnets—where permitting, purity specs, solvent extraction choices, waste handling, and IP constraints can change the economics.

REEx Implications—What’s Next?

If the U.S. wants a meaningful recycled Nd/Pr/Dy supply, policy should prioritize high-mass feedstocks (EV/HEV motors, later wind turbines), standardized collection contracts, and scalable disassembly systems—then validate the “winning” routes with pilot plants that publish real operating data (yields, reagent recycle, wastewater burden, and product specs).

Done right, recycling becomes a specialty-chemicals operation with tight specs, not a scrap-metal business—and EV/HEV magnets appear to be the first place where the math may finally work.

Citation: Laliwala, C., Amusat, O. O., Ojo, A., Garciadiego, A., Tarka, T., Bhattacharyya, D., & Torres, A. I. (2026). Design and optimization of processes for recovering rare earth elements from end-of-life permanent magnets. AIChE Journal. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1002/aic.70208 (opens in a new tab)

0 Comments

No replies yet

Loading new replies...

Moderator

Join the full discussion at the Rare Earth Exchanges Forum →