Highlights

- Europe is 100% dependent on China for heavy REEs (dysprosium, terbium) critical for EV motors and wind turbines.

- Major deposits in Sweden, Norway, and Greenland could transform this dependency if developed:

- Sweden: Norra Kärr, Per Geijer

- Norway: Fen Complex with 8.8M tonnes REO

- Greenland: Kvanefjeld, Tanbreez

- Sweden's Norra Kärr contains 51% heavy REEs and could become Europe's first heavy rare earth mine.

- Norway's Fen Complex—Europe's largest REE deposit at 559M tonnes—could supply 20-30% of EU demand by 2030-2035 if permitting advances.

- Economic viability faces challenges:

- 10-15 year permitting timelines

- Complex metallurgy

- Environmental concerns over radioactive by-products

- High capital costs

- EU policy initiatives and the Critical Raw Materials Act aim to fast-track strategic projects.

Europe is heavily dependent on imports for rare earth elements (REEs) – especially the heavy REEs like dysprosium (Dy), terbium (Tb), europium (Eu), and yttrium (Y) that are critical for high-strength magnets and other advanced technologies. At present, China supplies essentially 100% of the EU’s heavy REE needs, reflecting a major supply risk. Despite rising demand for EV motors, wind turbines, and electronics, there is currently no commercial rare earth mining in Europe. However, geological surveys have identified a number of REE-rich deposits across Europe. Many of these contain significant heavy REE enrichment, offering potential to diversify supply. Below we review the major known heavy rare earth deposits in Europe – focusing on their geology, locations, and what is known about their economic viability, mining status, and production potential.

Sweden: Kiruna’s Per Geijer Deposit

One of the most significant recent discoveries is the Per Geijer deposit (opens in a new tab) near Kiruna in northern Sweden. State-owned miner LKAB (opens in a new tab) announced in 2023 that exploration at Kiruna identified over 1 million tonnes of rare earth oxides (REO) in the Per Geijer orebody. Geologically, this deposit is unusual – the REEs occur in apatite (phosphate mineral) associated with Kiruna-type iron oxide ore. The apatite hosts high concentrations of REEs (locally reaching weight-percent levels) along with secondary minerals like monazite and allanite. While the REE mix skews toward light elements (such as neodymium and praseodymium needed for magnets), the deposit still contains notable heavy REEs as by-products. LKAB estimates that Per Geijer’s REO resource could satisfy a “large part of the EU’s future demand” for rare-earth magnets.

In terms of development, Kiruna’s REE deposit remains at an early stage. State-owned LKAB has begun preliminary mine planning (including driving an exploration drift 700 m deep toward the deposit) and aims to apply for an exploitation concession in 2023. However, environmental permitting in Sweden is lengthy – LKAB projects it could take 10–15 years before mining and REE production can begin. If brought to production, Per Geijer could become Europe’s first major rare earth mine, producing REEs (including some heavy REEs like Dy, Tb in minor quantities) as by-products of iron ore and phosphate extraction.

Sweden: Norra Kärr Heavy REE Deposit

Another Swedish deposit of strategic importance is Norra Kärr, (opens in a new tab) located in southern Sweden near Gränna. Norra Kärr is a small Mesoproterozoic alkaline nepheline syenite intrusion enriched in zirconium and REEs, with the unusual mineral eudialyte as the main REE-bearing phase.

Norra Kärr, Sweden

Crucially, about 51% of its rare earth oxide content is heavy REEs – making it one of the richest heavy REE deposits in Europe. A NI 43-101 compliant resource estimates 41.6 million tonnes at 0.57% TREO (total REO), containing substantial dysprosium and terbium output potential. In fact, projections suggest an annual production of ~248 tonnes of Dy oxide and 36 tonnes of Tb oxide over Norra Kärr’s first 26 years, which could significantly bolster Europe’s heavy REE supply.

Despite its high strategic value, Norra Kärr has faced permitting delays. The deposit was first identified by the Swedish Geological Survey over a century ago, and declared a site of National Interest in 2011 due to its importance for Sweden and the EU. Junior miner Leading Edge Materials has been advancing the project, but mining licenses have been slow due to environmental court challenges (the site is near a sensitive lake and Natura 2000 areas). As of late 2025, the company submitted supplementary information for its mining lease application, and authorities are reviewing it. If approved and developed with modern processing (eudialyte concentrate production and REE separation), Norra Kärr could become Europe’s first heavy rare earth mine, providing a long-term source of Dy, Tb, and other critical heavy REEs.

Asidefrom Norra Kärr, Sweden hosts other REEoccurrences: for example, the Olserum project (opens in a new tab) (also in southern Sweden) is a smaller deposit with an estimated 4.5 Mt at 0.6% TREO and a high proportion of heavy REEs (notably Dy/Tb). Sweden’s classic iron mines (Kiruna, Malmberget) and historical Bastnäs district (opens in a new tab) also contain REEs (indeed, many rare elements like yttrium, erbium, holmium were first discovered in Sweden), but those were not developed for REE extraction in the past. Today, Sweden’s combination of large REE resources in Kiruna and heavy-enriched deposits like Norra Kärr and Olserum positions it as a potential cornerstone of European REE supply once mining permits are secured.

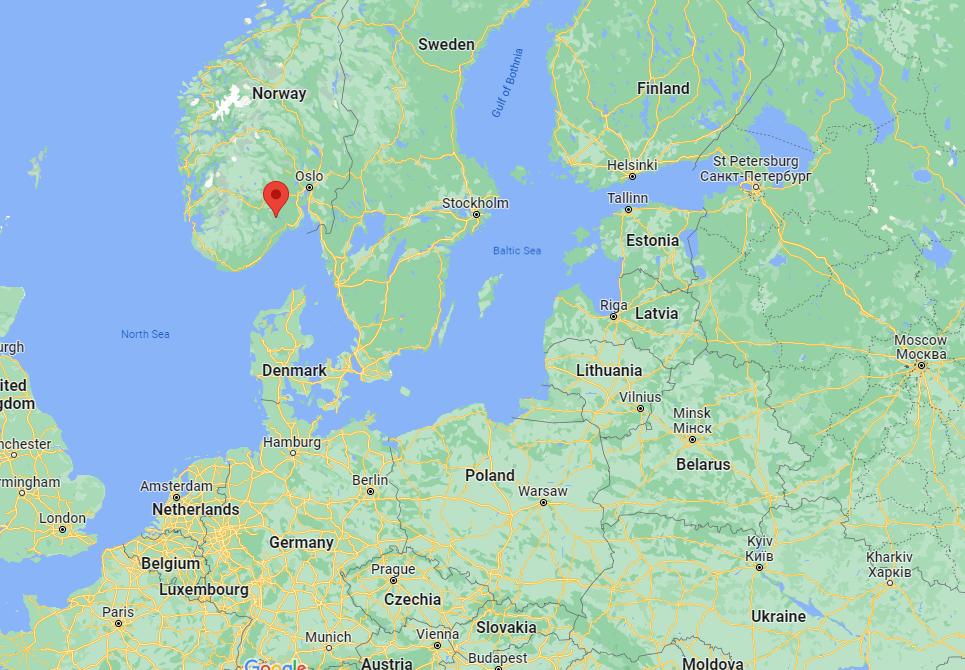

Norway: Fen Carbonatite Complex

Norway has emerged with a record-breaking rare earth deposit at the Fen Complex in Telemark, about 150 km southwest of Oslo. The Fen Complex (opens in a new tab) is a Proterozoic carbonatite–alkaline intrusive complex long known for niobium; recent exploration by the company Rare Earths Norway (opens in a new tab) has confirmed it also hosts an enormous REE resource. In June 2024, a maiden JORC-compliant resource was announced for Fen: 559 million tonnes grading 1.57% TREO, containing about 8.8 million tonnes of rare earth oxides. This makes Fen the largest known REE deposit in continental Europe by a wide margin.

The Fen Complex, Norway

Within this resource, roughly 1.5 million tonnes are magnet-related rare earths (the Nd, Pr, Dy, Tb crucial for EV motors and wind turbine magnets). The geology of Fen is similar to large carbonatite deposits elsewhere (like Bayan Obo in China): REEs are concentrated in carbonatite and associated minerals (bastnäsite, monazite, etc.), and the distribution is LREE-rich but with significant heavy REE in the form of yttrium and others present in the ore.

While Fen’s size and grade are impressive – potentially capable of meeting a large share of Europe’s demand – its development is still at an early stage. The deposit extends deep underground (the current resource goes down to –468 m, with mineralization open to ~–1000 m). Mining will likely require underground methods; Rare Earths Norway is investigating methods to exploit Fen with minimal environmental impact.

The discovery has drawn support from European raw materials initiatives: EIT RawMaterials (opens in a new tab) and the European Raw Materials Alliance (opens in a new tab) (ERMA) have backed the project as a pillar of a secure EU REE supply chain. With an inferred resource now defined, the next steps include detailed feasibility studies, environmental assessments, and permits.

If successfully developed, the Fen mine could supply an estimated 20–30% of Europe’s rare earth demand by 2030–2035. Importantly, it would also yield some heavy REEs(though the majority of output by volume would be light REEs likecerium, lanthanum, neodymium). As ERMA’s CEO noted, projects like Fen are “world-class” opportunities that could transform Europe’s rare earth self-sufficiency if fast-tracked.

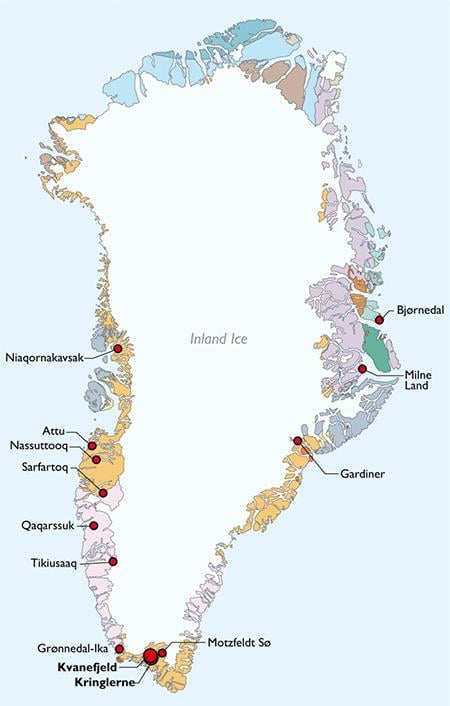

Greenland (Denmark): Kvanefjeld and Tanbreez

Politically linked to Europe via Denmark, Greenland holds two of the world’s most significant rare earth deposits in the Ilímaussaq complex of south Greenland. The first is Kvanefjeld (Kuannersuit), (opens in a new tab) a giant layered peralkaline intrusion known for its unique geology and size. Kvanefjeld’s ore is hosted in lujavrite (an agpaitic nepheline syenite) and enriched in both light and heavy rare earths – rare minerals like steenstrupine and eudialyte contain not only large quantities of neodymium and praseodymium but also notable dysprosium and terbium. Total JORC resources (including neighboring zones) are on the order of 1 billion tonnes at ~1.1% TREO, equating to ~11 million tonnes of REO – one of the largest accumulations globally. This deposit could theoretically produce ~32,000 tonnes of REO per year (about 12–14% of world supply) at full scale. Crucially for heavy REEs, Kvanefjeld’s REE distribution is more balanced than many giant deposits: it has a higher share of mid-to-heavy REEs compared to typical light-REE-rich projects. In other words, alongside abundant Nd-Pr for magnets, it contains sizable Dy and Tb resources – metals critical for high-temperature magnets in wind turbines and EVs.

Greenland Rare Earth Deposits

Despite advanced studies (a feasibility and environmental impact assessment were completed by the mid-2010s), Kvanefjeld’s development is currently stalled. The project faces strong environmental and political opposition in Greenland, largely due to its significant uranium content (the ore contains ~300 ppm U₃O₈, making uranium a co-product). Greenland’s government instated a uranium mining ban in 2021, which directly impacted Kvanefjeld. The owner company (Energy Transition Minerals, formerly Greenland Minerals) is now in legal arbitration with Greenland/Denmark over its license. Thus, while Kvanefjeld could be a game-changer for Europe’s rare earth supply (including heavy REEs), its economic viability is on hold pending regulatory resolution and social license to operate.

Adjacent to Kvanefjeld is the Tanbreez (Kringlerne) deposit (opens in a new tab), another huge REE resource in the Ilímaussaq complex. Tanbreez contains extensive eudialyte-rich zones with very low uranium content, focusing on rare earths, zirconium, and tantalum. This project (held by a private company) has reportedly received an exploitation license from Greenland’s authorities, since it avoids the uranium issues that plague Kvanefjeld. Tanbreez’s total REE resource is likewise massive (on the order of billions of tonnes of rock, with multi-million tonnes of REO) and is enriched in heavy rare earth elements due to the eudialyte mineralogy. If Tanbreez proceeds to development under its

U.S.-backed ownership, it could become a major non-Chinese source of heavy REEs for Western markets. Both Greenland projects underscore that substantial heavy REE reserves exist within greater Europe, although geopolitical and environmental factors will determine if they can contribute to supply.

Finland: Sokli and Other Deposits

Finland has several REE-bearing deposits, though none in production yet. The most notable is the Sokli carbonatite complex i (opens in a new tab)n northern Finland (part of the Devonian Kola alkaline province). Sokli contains a large phosphate (apatite) deposit with notable enrichment in niobium, tantalum, and rare earths. Drilling has revealed late-stage carbonatite veins at Sokli with high REE grades of 0.5–1.8% TREO in places. The REE mineralization at Sokli is dominated by light REE minerals (ancylite-(Ce), bastnäsite-(Ce), monazite) and strontium-rich apatite, indicating a light-REE-rich profile. Heavy REEs are less abundant there, but some yttrium and others occur in accessory phases. The Sokli deposit was studied as a source of fertilizer phosphorus by Yara, and though mining plans were put on hold, there is potential to extract REEs as a by-product of any future phosphate operation.

Historically, Finland was actually one of the only European countries to produce any rare earths: the Korsnäs mine (opens in a new tab) in western Finland (a small Pb-REE deposit) yielded about 36,000 tons of rare-earth–rich concentrate between 1963 and 1972 as a by-product of lead mining. That operation recovered primarily light REEs (lanthanum, cerium) from monazite.

Today, aside from Sokli, Finland has other minor prospects – e.g., the Katajakangas occurrence (a Nb-Y-REE enriched granite with an estimated 0.46 Mt resource containing yttrium and heavy REEs). While these are relatively small, they demonstrate the presence of heavy REEs (yttrium, gadolinium, etc.) in Finnish bedrock. In summary, Finland’s REE resources are not as large as Sweden’s or Greenland’s, but they could provide a supplemental heavy REE supply in the future, especially if integrated into other mining projects (phosphate, Nb-Ta mining, or even extraction from mine tailings).

Other European REE Occurrences

Beyond the Nordic countries, REE deposits in the rest of Europe tend to be smaller or less developed, but are worth noting for completeness.

In Southern Europe, some alkaline igneous complexes in the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal) host REE occurrences – for example, the Ordovician peralkaline Galiñeiro complex inGalicia, Spain, has patchy zones with >1% total REE and notableheavy-REE enrichments (with minerals like xenotime, a Y-Dy phosphate). Likewise, small carbonatite dikes in Spain’s Canary Islands (Fuerteventura) contain up to ~0.5–0.7% TREO with a mix of REE phosphates and carbonates. These are geological curiosities at this stage, not economic deposits.

Some placer deposits (alluvial or beach sands) in Europe also concentrate rare-earth-bearing minerals. For instance, in Greece and Serbia, heavy-mineral sands and paleo-placers have been found to contain monazite and xenotime grains.

One example is the Ordovician-aged heavy mineral quartzite in Portugal’s Portalegre area (opens in a new tab), which extends into Spain: it contains disseminated monazite with an estimated resource of 2.4 Mt at 0.46% TREO. Such placers typically yield mixed REEs (monazite being rich in light REEs, xenotime providing yttrium and heavy REEs), but so far none have been mined for REEs in Europe.

Additionally, bauxite deposits and red mud (bauxite processing waste) in the Mediterranean region are known to be enriched in rare earth elements, including some heavy REEs. Research initiatives (like the EU EURARE project) have investigated extracting scandium and REEs from Greek bauxite residue, as one potential secondary source. While promising for the circular economy, these are not primary “deposits” per se and require technological development to be viable.

Finally, it’s worth mentioning as Rare Earth Exchanges™ has reported that in Turkey(which straddles Europe and Asia), a very large rare earth-bearing deposit was reported in 2022 near Eskişehir. Turkish authorities announced a reserve of 694 million tonnes of ore containing rare earth elements, purportedly the world’s second-largest after China. However, the details suggest the ore is of relatively low grade and mostly light REEs; the heavy REE content and economic recoverability remain uncertain. Turkey’s find, if developed, could eventually contribute to Europe’s supply, but as of now, it underscores that significant REE resources (light and heavy) exist on Europe’s periphery.

Economic Viability and Outlook

Developing heavy rare earth deposits in Europe faces both opportunities and challenges. On one hand, the identified deposits (Sweden’s Per Geijer and Norra Kärr, Norway’s Fen, Greenland’s Ilímaussaq deposits, etc.) are of sufficiently large scale and grade to potentially supply a major share of Europe’s REE demand for decades. If even a few of these projects come to fruition, Europe could reduce its near-total dependency on Chinese heavy REEs. For example, the Fen project alone might supply ~30% of Europe’s rare earths and meet a large portion of heavy magnet metal needs by the 2030s. The EU is pushing policy measures (the Critical Raw Materials Act and investment alliances) to expedite such projects. There is also growing interest in downstream processing (separation facilities and magnet manufacturing) so that European mines can feed a full domestic supply chain.

On the other hand, economic and permitting hurdles are significant. Many European REE deposits come with complex metallurgy (e.g., refractory minerals like eudialyte or apatite that require innovative extraction techniques) and sometimes radioactive by-products (thorium or uranium) that raise environmental concerns. Obtaining social license for mining is challenging in countries with strong environmental regulations, as seen with the delays at Norra Kärr and Kvanefjeld. The typical timeline from discovery to production in Europe can exceed 10–15 years, which is at odds with the immediate supply needs. Moreover, capital expenditure to develop these deposits (and associated processing plants) is high, and securing financing may require public-sector support or partnerships, given past volatility in REE prices.

Final Thoughts

Europe does possess notable deposits of heavy rare earth elements across its territory. Sweden and Norway’s recent finds, along with Greenland’s vast resources, could theoretically make Europe a significant producer of both light and heavy rare earths in the future. These deposits cover a range of geological settings – from Scandinavian carbonatites and alkaline complexes to apatite iron ores – and contain the critical heavy REEs needed for high-tech industries. Realizing their potential will depend on successfully navigating the feasibility and permitting processes. Should even a few of these projects reach production, Europe could secure a domestic source of heavy rare earths, improving its economic resilience and supporting the green transition. For now, all eyes are on pilot projects and mining approvals in the coming years, as Europe seeks to turn its geological endowment into a strategic advantage.

Sources: European Commission & ERMA reports; LKAB, Rare Earths Norway and Leading Edge Materials press releases; EuRare project data; WEF and Reuters news analyses, among others.

0 Comments

No replies yet

Loading new replies...

Moderator

Join the full discussion at the Rare Earth Exchanges Forum →