Highlights

- Malaysia maintains its ban on unprocessed rare earth exports despite signing a critical minerals pact with the US, requiring all rare earth materials to be processed domestically before export to capture higher economic value.

- The US-Malaysia deal is complementary rather than contradictory—Malaysia will supply processed rare earth products like oxides and alloys to America, not raw ore, positioning itself as a strategic bridge between China and the West.

- Malaysia's policy attracts investment from both Eastern and Western partners, with companies like Lynas Rare Earths already operating major processing facilities and new ventures like DTEC MMT establishing mining and value-added operations in the country.

Malaysia is holding firm on its policy of the banning of unprocessed rare earth element (REE) exports even after signing a new critical minerals pact with the United States (opens in a new tab) as reported on by Rare Earth Exchanges. Investment, Trade and Industry Minister Tengku Zafrul Aziz (opens in a new tab) reaffirmed in parliament that no “raw” rare earths will leave Malaysia’s shores, emphasizing the need to protect domestic resources and spur local value-add. This stance appeared to conflict with a U.S.–Malaysia joint statement – inked during U.S. President Donald Trump’s visit to Kuala Lumpur – in which Malaysia “agreed not to prohibit or restrict the export of critical minerals or rare earth elements to the U.S.”.

Table of Contents

However, officials stress that the deal will be implemented in line with Malaysia’s laws and policies, meaning the country will still only allow exports of rare earths after value is added domestically, as cited (opens in a new tab) in The Edge Malaysia.

Minister Tengku Zafrul Aziz---Malaysia Seeks Value-Added and Open for Business

The joint statement notably did not specify whether Malaysia’s pledge covered raw ore or processed materials, giving Kuala Lumpur leeway to honor its U.S. commitments through exports of processed REE products rather than shipping cheap concentrates.

Value-Add Focus: Raw vs. Processed

Cited in Reuters (opens in a new tab), Minister Tengku Zafrul was explicit that Malaysia “no longer [wants] to be a country that only digs and ships out cheap raw materials”. The policy bans exports of unprocessed rare earth ores or concentrates, echoing an earlier announcement by Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim that such exports would be stopped to avoid “unrestricted mining and export” that depletes critical minerals.

Once materials are refined or processed in-country, Malaysia is open to exporting the higher-value products as part of global supply chains. As covered in Shanghai Metals Market (opens in a new tab), “Our policy is not to prevent trade forever… It is to prevent the export of cheap, unprocessed raw materials so that value is added to Malaysia,” Tengku Zafrul explained.

In practice, this means rare earth oxides, metals, or magnet components produced in Malaysia can be sold abroad – but shipping out ore or mixed REE concentrate is off-limits. By encouraging foreign investment and technology transfer for onshore mining and refining, Malaysia aims to develop an integrated domestic rare earth industry instead of remaining an extractor of raw minerals.

Rare Earth Exchanges reported that China was contemplating the licensing of processing technology to the Southeastern Asian nation.

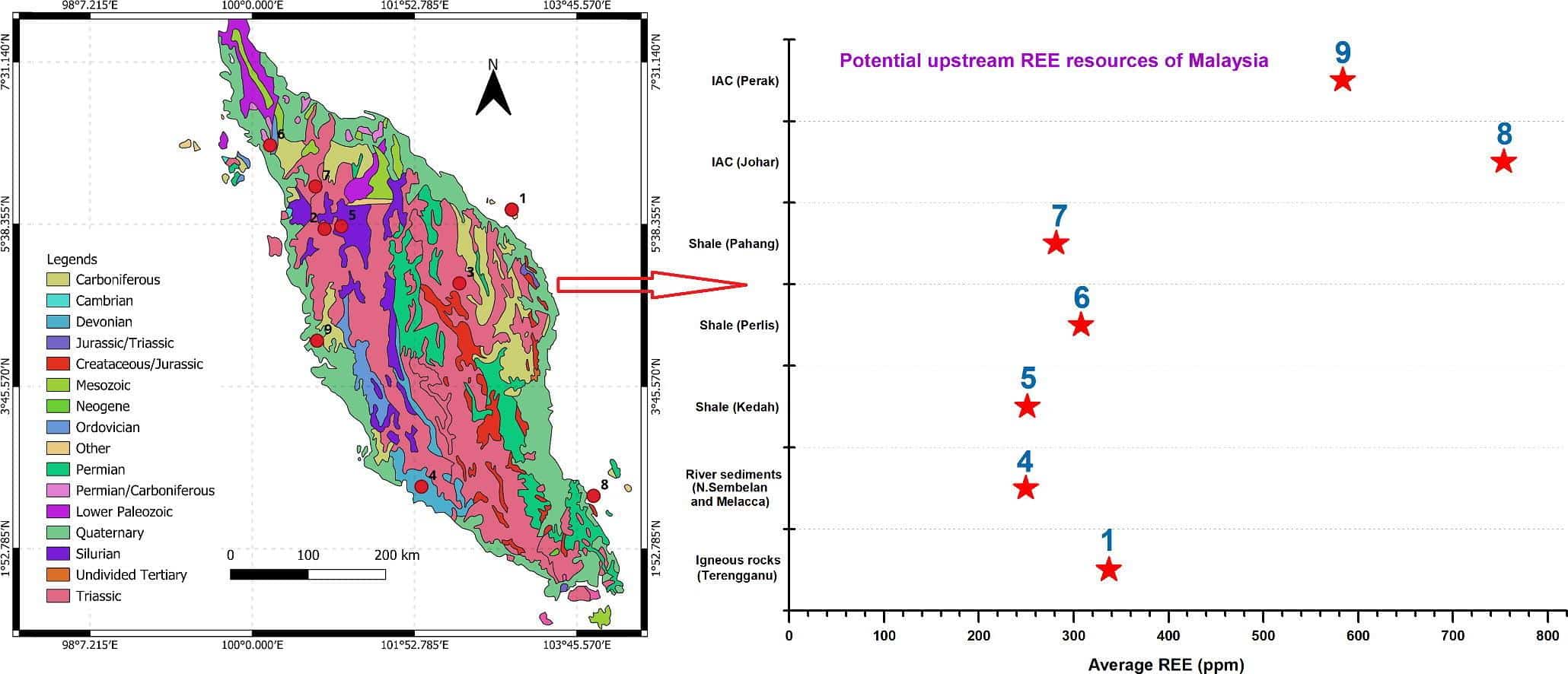

The country’s estimated 16.1 million tonnes of rare earth deposits will thus only be tapped in partnership with firms that establish local processing, ensuring Malaysia captures more economic benefit.

U.S. Deal: Strategic Alignment or Contradiction?

Despite initial confusion, Malaysia’s ban and the U.S. critical minerals deal are being portrayed as complementary, not contradictory by officials. The U.S.–Malaysia agreement on critical minerals – part of a series of pacts Washington signed with Southeast Asian nations to diversify supply chains amid China’s tightening export curbs – obliges Malaysia to refrain from imposing export bans or quotas specifically toward the U.S.

Malaysia can uphold this by supplying the U.S. with processed rare earth products rather than raw ore, which aligns with its domestic policy of value addition. “Our policy… applies to REE and critical minerals. Once processed domestically… high-value downstream products can then be exported,” Zafrul noted in The Edge Malaysia (opens in a new tab), indicating that the U.S. deal will be carried out in this spirit.

In other words, American industries may eventually buy rare earth materials from Malaysia, but likely in the form of oxides, alloys or magnets produced on Malaysian soil. Analysts say these new memoranda of understanding will take time to bear fruit – significant exports to U.S. buyers will require scaling up Malaysia’s mining and refining capacity first.

Still, the agreement positions Malaysia as a potentially important alternative source for U.S. manufacturers if Chinese supplies falter as even pointed out by South China Morning Post (opens in a new tab). It also dovetails with Malaysia’s goal of attracting investment: “Malaysia welcomes strategic cooperation with the U.S. as well as other countries in developing the domestic REE industry,” Tengku Zafrul said, citing a potential tripartite partnership with the U.S. and Australia.

Impact on Lynas and Allied Supply Chains

Malaysia’s policy has direct implications for Lynas Rare Earths, the Australian company operating a major REE processing plant in Kuantan. Lynas – the largest rare earth producer outside China – imports concentrate from Australia and refines it in Malaysia, exporting separated oxides to global customers. Since Lynas already performs value-added processing locally, it is largely unaffected by the export ban on raw material.

In fact, Malaysia’s value-first mandate aligns with Lynas’ operations and future plans. The company recently announced a new heavy rare earth separation facility in Malaysia, a A$180 million project to produce up to 5,000 tonnes per year of heavy REE oxides like dysprosium and terbium.

Feedstock will come from Lynas’s Mt Weld mine and other sources, with the first output (samarium) expected by 2026. This expansion, encouraged by rising demand for non-Chinese heavy REEs, strengthens Malaysia’s role as a downstream hub. Minister Zafrul even highlighted Lynas as an example of U.S.-Australia-Malaysia collaboration in building a domestic rare earth ecosystem, as pointed out in The Edge Malaysia.

Nevertheless, Lynas has faced regulatory hurdles, as pointed out (opens in a new tab) in Reuters – Malaysia only granted it a license extension to 2026 on the condition that it removes radioactive waste from its feedstock. The government’s stance indicates “it’s not a softening of position” on safety, but rather a controlled path allowing Lynas to continue operating while meeting stricter processing standards. With those conditions met, Lynas’ presence is seen as mutually beneficial: it provides Malaysia with technology and jobs in exchange for a stable operating base.

Other U.S.-aligned downstream projects could be drawn to Malaysia under the new policy climate. Rare Earth Exchanges has covered the major mining operation, Southern Alliance Mining (opens in a new tab) (SAM).

A Malaysia-based company focused on mining, exploration, processing, and selling mineral properties, primarily iron ore from its Chaah Mine, SAM also produces crushed iron ore for pipe coating and mines other materials like gold and rare earth elements. The company's strategy involves developing long-life assets, employing innovative technologies, and seeking growth through both its current operations and diversification, including a planned shift into rare earth elements.

Chief Operating Officer Wei Hung Lim (opens in a new tab) shared with Rare Earth Exchanges on a phone call that currently, all rare earth element exports from Malaysia go to China. However, the SAM Chief Operating Officer shared, “We are open to working with everyone.”

Kuala Lumpur’s policy-based insistence on in-country processing is a signal to any foreign miner: to access Malaysia’s REE deposits, one must build refining or manufacturing facilities locally. This could invite partnerships with Western firms to develop Malaysia’s sizable ionic clay reserves (notably rich in heavy rare earths) that have so far been untapped. Indeed, reports (opens in a new tab) suggest Malaysia’s sovereign fund Khazanah (opens in a new tab) is evaluating a joint venture with a Chinese company to build a rare earth refinery on Malaysian soil. Such a move would rapidly boost Malaysia’s processing know-how, though it underscores a strategic “coopetition” – Malaysia is courting both Chinese and Western investment in its rare earth sector.

Rare Earth Exchanges highlighted the new Malaysian-American-owned venture, DTEC Mineral & Metal Technology (MMT), which announced they will be establishing a mining and value-added activity in Malaysia. This would be a first.

For the U.S. and its allies, supporting Malaysian downstream projects (e.g., funding new plants or sharing extraction technology) could secure them a non-Chinese source of critical minerals in return. As one analyst noted, if downstream processing is put in place and long-term offtake deals are arranged, Malaysia and Thailand could help reduce U.S. dependence on China for magnet materials in the coming years.

Strategic Outlook

Malaysia’s rare earth export ban — a core policy objective — remains firmly in place despite the new U.S. critical minerals deal. The decision underscores Kuala Lumpur’s determination to move up the value chain rather than revert to its old role as a raw material exporter.

As Rare Earth Exchanges has previously chronicled, this moment marks a historic inflection point for Malaysia. The nation stands poised to become a strategic interface between China and the United States — a bridge in the global rare earth supply chain where industrial policy, technology transfer, and geopolitics now converge.

By leveraging its policy in negotiations, Malaysia won recognition as a “trusted supply chain partner” under the U.S. trade framework, as the White House reported, without ceding its resource strategy. In the near term, little will change – no raw REE will be exported, and any U.S.-bound shipments will be limited to what Malaysia can process, currently via Lynas.

Over the medium term, however, the landscape could shift as investments materialize—see the table below:

| Strategic Dimension | Analysis and Implications |

|---|---|

| Expanded Processing Capacity | New joint-venture refineries and separation plants — whether in partnership with Australian, American, or Chinese firms — could soon come online, positioning Malaysia as a regional rare earth processing hub. This would allow the country to produce and export greater volumes of REE oxides and alloys to the U.S. and other markets without breaching its ban on raw exports. |

| Upstream Development | Should Malaysia begin mapping and extracting its estimated 16 million tonnes of rare earth reserves, current policy ensures all ore will be refined domestically (or at least that is the stated intention). Future mining projects will likely include onshore processing facilities, strengthening Malaysia’s industrial base, creating skilled jobs, and deepening technological expertise. |

| Supply Chain Diversification | For Washington, the Malaysia deal is part of a broader effort to secure critical minerals from allied nations. While it may not yield large-scale supply immediately, it sets the foundation for diversification. If Malaysia successfully builds an integrated REE value chain, U.S. manufacturers could access magnet materials insulated from geopolitical disruption. |

| Geopolitical Balancing | Malaysia’s balanced stance attracts capital from both East and West. By engaging with the U.S. on critical minerals, Kuala Lumpur gains leverage and strategic alternatives beyond Beijing’s orbit — even as it continues project talks with Chinese entities. This non-aligned strategy may provide Malaysia a stronger bargaining position in economic and geopolitical arenas. |

Conclusion

Malaysia’s ban on exporting raw rare earths remains firmly intact – a cornerstone of its resource policy. The recent U.S.–Malaysia critical minerals deal does not overturn this ban but rather operates within it, focusing on collaboration to develop Malaysia’s downstream REE capabilities rather than opening the floodgates to unprocessed exports.

As Malaysia moves to harness its rare earth wealth, the world will be watching how this policy plays out. Will Kuala Lumpur successfully foster a homegrown REE processing industry and become an indispensable link in the global supply chain? The answer will shape not only Malaysia’s economic future but also the geopolitical calculus of rare-earth security in a world increasingly seeking alternatives to China’s dominance.

0 Comments